By Peter Judge

Agriculture has long been the backbone of Vanuatu, providing livelihoods and food, playing a key cultural role, and providing an invaluable connection to nature. The fact that 85% of the population says they have access to customary land, with 94% of these saying that it is enough for their needs, is one of the bedrocks of what makes Vanuatu such a wonderful country.

And whilst this should all be celebrated, it must also be recognised that the sector faces a multitude of challenges, from low productivity and limited access to modern technology to reliance on imports and high inflation.

In the past 60 years, global agricultural yields have boomed, as the ‘Green Revolution’ has turbocharged farming. As just one example, since 1961 land used for cereals globally has increased by just 13% but output has increased by 249%. This has been mostly driven by improved genetics, fertiliser, scale-farming, and technology. This has allowed humanity to feed the 8 billion people that are alive today (although of course often at a massive environmental cost).

However, very few of these improvements have reached Vanuatu. Here the norm remains micro-farms with no improved genetics, no or only very basic technology, no use of data, and no fertiliser.

This limits the productivity of the agricultural sector. Despite soil where you can drop a seed and it will grow and 70-80% of the country being engaged in it, the primary sector accounts for just 20% of GDP. About half of calories are imported, even as Vanuatu exports basically no food products.

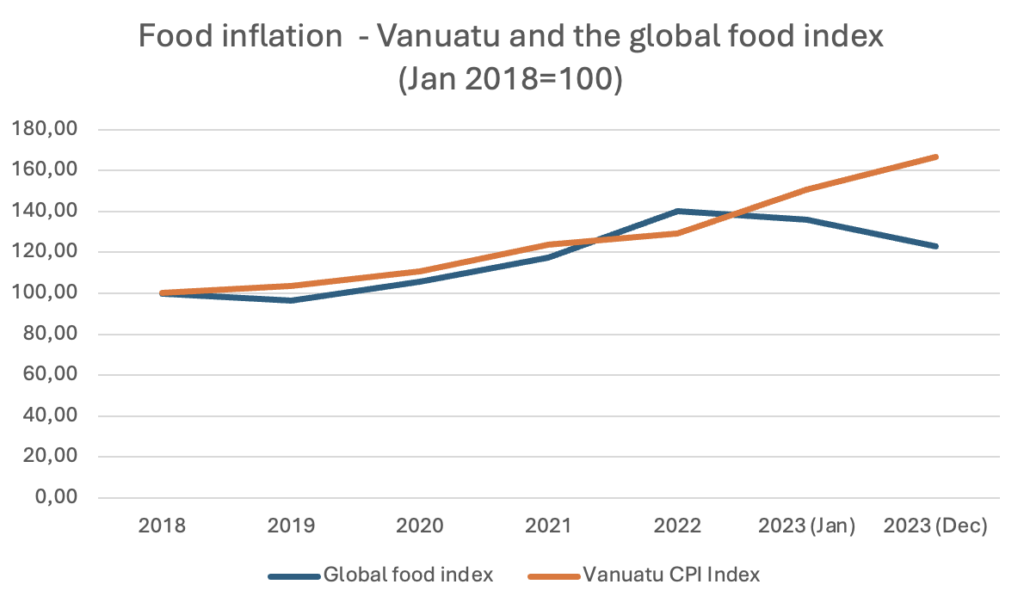

The low productivity and exposure to imports also means that food inflation is high, with cumulative food inflation in Vanuatu at 67% since the start of 2018, and 29% since the start of 2022 (even as global food prices have fallen 12%). This is of course particularly damaging for the poor.

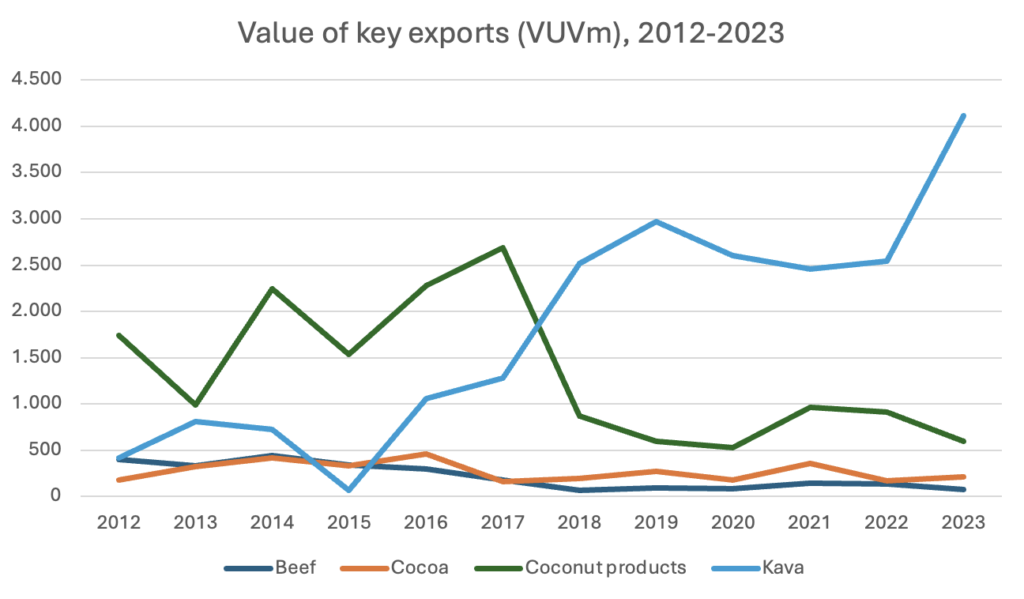

That is not to say there has not been any success. There are a small number of farms who are increasingly moving to scale. Kava has boomed (exports were approx. VUV 4 billion last year and the domestic market is far larger). Returns are high to farmers and kava has the potential to drive development to the islands like nothing else.

However, other key exports have all fallen since 2014 – notably cattle (down 84%) coconut products (down 73%) and cacao (down 48%). Fruit and vegetables are expensive with fragile supply often limited to short-growing windows. This raises concerns about people’s ability to eat healthily and also limits what manufacturing businesses can achieve. This is all despite billions of vatu of aid being put into these sub-sectors (whereas kava has received basically no support and exports have grown by over 400% since 2014).

In addition, there is also now just one major egg producer, and the increasing cost of energy and feed has led to much higher egg prices. Pork production remains scarce, and small-scale fishing is increasingly under pressure from declining catches.

Given such major and rapid global changes, especially the climate crisis, and a rapidly growing domestic population (including continuing urbanisation), then one of the biggest policy questions is how Vanuatu will sustainably feed itself.

The first point to make is we need better data to guide us. The Agricultural Census was conducted in 2022 but the findings have not been released, and this makes planning and analysis very challenging.

Otherwise, the most basic step is to allow improved genetics into the country. This can be done entirely safely is the easiest overnight way to increase yields.

In addition, some form of larger scale farming is clearly needed. But how do we get there?

One idea is to identify a number of champion farmers with the aim being that they end up successfully running a set of a commercial farm of 5-10 hectares, with a particular focus on growing fruits and vegetables for the domestic market. Some possible features could include:

- A five year training course at Vanuatu Agricultural College designed to teach all the necessary skills. This could go for six months of the year;

- The other half of the year the farmers could go to partner farms on seasonal work who would develop their skills and knowledge. This would also enable the individuals to build the deposit necessary for the farm loan;

- NBV could purchase the land, build a house on it, and be responsible for selling it to the farmers, managing the loan, and providing business support;

- The Government should provide simple and clear support: for example with supporting the cost of the set-up of the farm (but no ongoing support) or by guaranteeing the loan to reduce interest costs;

- These farms could be clustered together, allowing them to share key resources – such as tractors, technology, knowledge, and labour.

The first question is where does the land come from? To make the businesses work it must be good farming land with access to market and water and without land disputes.

One option is to identify and clear land and start from scratch. This would be difficult and expensive and obviously we don’t want to be cutting down trees if at all avoidable.

Another option is to consider whether there is any existing farmland which could be repurposed. Options include land from those businesses developed at great expense which now produce basically nothing (such as Mentensel Plantations), or many of the cattle farms.

This is because it is a simple fact that there is no pathway to a sustainable future without a sharp decline in the cattle industry. It drives 40% of global deforestation, consumes 41% of cereals grown, uses 55% of freshwater withdrawals, and is responsible for about 15% of the global emissions footprint.

If beef farming were to stop (but dairy and other meat continued) it is estimated that the amount of land used for farmland could halve. For the simple sake of our futures, the world needs to eat way less beef.Of course, what needs to happen at the global level isn’t necessarily the case here. Vanuatu is a net carbon sink and Vanuatu must do what is best for Vanuatu’s development – but still, from this perspective, cattle is clearly not the future. This is because it is so wildly inefficient.

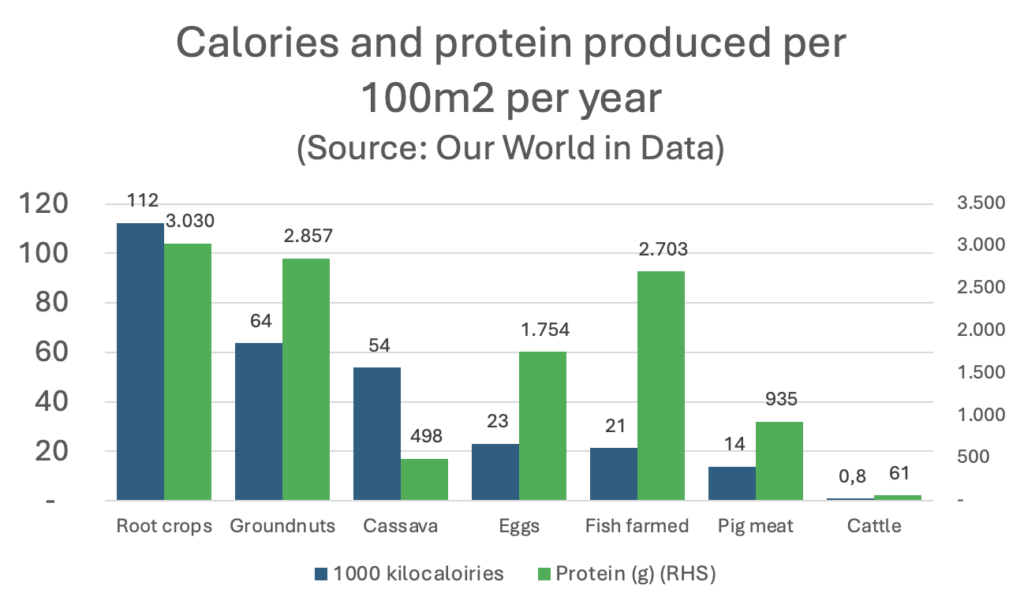

For every 100 kilocalories you feed a cow, you get just 2 back to eat. Other animal crops are much more efficient (pork is 9, poultry 13, and eggs 19). Cattle requires 134 times more land than root crops to produce the same number of calories.

Cattle farms also provide very few jobs. A 1,500-hectare cattle farm for cattle may only employ 20 people, often on minimum wage. If this land was used for fruit and vegetable production, then it could support hundreds, including hopefully creating numerous medium-scale ni-Vanuatu owned businesses.

Cattle production has declined 47% since 2010, and it provides just 1.2% of Vanuatu’s calories. Much of the cattle land is in poor condition and is getting worse. At a small scale (under 50 head) the economics of the business often don’t add up.

If the goal is to provide affordable and protein-rich food, then pigs, chickens, and fish farms are far better options.

In order to make businesses work at scale, then a commercial domestic stock feed industry is needed. The power of renewable energy must also be unleashed to help these businesses run cheaply.

Of course, if there is to be a transition from cattle to small commercial farms, then the current landowners will have to be fairly compensated, something which has to be carefully thought through and managed.

The purpose of this article is also not to criticise cattle farmers, nor to downplay its historical or cultural role, or to say that there should be no cattle. Some land is not suitable for crops, and there is a place for a niche industry providing the highest-quality beef. Furthermore, micro-herds for cultural or individual food security reasons obviously have a role.

But the facts are definitive: cattle is not a growth industry and cannot play a leading role in ensuring Vanuatu’s food security.

Any systematic change must also make sure that micro farms still have sufficient opportunities. This is where encouraging value-addition (i.e. creating a more certain demand) and high-value cash crops (especially kava) will be paramount.

The primary sector has immense potential for growth and improvement and has a crucial role in making Vanuatu have a better development journey. To unleash this potential will require a long-term strategy, dedication and hard work, and major investment – in technology, infrastructure, but above all in people.

Peter Judge is Director of Economics and Research at Pacific Consulting Limited and author of the recent VCCI Private Sector Economic Outlook.