By Sela Molisa

Editor’s note: In October 2021, The Pacific Advocate reported that the European Union blacklisted several Pacific nations that “encourage abusive tax practices”. Following this report, the Financial Centre Association of Vanuatu hit back, accusing the EU of bullying smaller Pacific Island countries. Now a former prominent MP from Vanuatu has launched another scathing attack on Europe, singling out France.

Among the nine jurisdictions singled out by the European Union for their “abusive tax practices”, no less than six are small, Pacific island nations with underdeveloped economies. As unlikely as it seems, Brussels’ obsession with the region looks like it has less to do with the noble fight against tax evasion and more with geopolitical self-interest.

Launched in 2017 and updated twice a year since, the EU’s “list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes” (a.k.a. the Tax Blacklist) aims to tackle tax fraud, evasion or avoidance and money laundering by naming and shaming the places that facilitate such activities and might erode the EU members’ corporate tax revenue.

Surprisingly, with the sole exception of Panama, the Tax Blacklist includes none of the top 70 corporate tax havens ranked by the Tax Justice Network in 2021, nor any of the jurisdictions flagged for sheltering private wealth in the recent Pandora Papers (except for Samoa). Instead, the EU only finds risk for tax abuse in three jurisdictions in the Caribbean (Panama, U.S. Virgin Islands, Trinidad & Tobago), and six in the Pacific.

The six – American Samoa, Fiji, Guam, Palau, Samoa and Vanuatu – are collectively home to 1,644,076 people, or 0.02% of currently living humans, who produce about 0.1% of global GDP. They are but a flyspeck on the world economy by most financial metrics. Still, the EU expects the public to seriously believe that this group of islands forms the single gravest threat to its member states’ tax revenue base.

Easy targets

Why such a disproportionate focus on the Pacific? One explanation would be to look at the Tax Blacklist as a tool not against tax evasion, but against tax insubordination. Any country that doesn’t adopt European big-government tenets – big taxation, big spending – becomes an adversary for the Union in the global competition for investment.

The EU would certainly face a backlash if it publicly challenged the fiscal policies of the large and powerful tax havens where EU citizens actually shelter their wealth. These of course include Hong Kong and the British Virgin Islands as well as its very own members and neighbours like Luxembourg, Netherlands, Cyprus, Monaco and Switzerland, to name a few. Instead, Brussels saves face by targeting smaller, emerging competitors that do not have the resources or the connections to defend themselves.

What these Pacific Islanders do have in common is not a boundless capacity to shelter tax, but a defencelessness against European bullying. In the end, the Tax Blacklist aims at only the low hanging fruit: weak nations that refuse to toe the EU line on tax. The entire exercise amounts to nothing but theatre for the European taxpayer – with a touch of nostalgia for colonial times.

Not our cup of tax

It should go without saying that fiscal policies which are sound in a large, developed European nation do not necessary make sense in small Pacific Island countries. Depending on their circumstances and degree of development, they have a range of options to generate public revenue in ways that best address their specific challenges.

Take Vanuatu. It never had an income tax, neither before nor after it gained its independence in 1980. As a small offshore financial centre, it offers an attractive environment for foreign investors. For this isolated country with limited resources, attracting FDI is key to diversifying the economy and bringing in foreign currencies. It hardly makes it a prime business destination though; the country’s GDP hovers under just 1 billion USD, and that’s pre-Covid.

Actually, the business-friendly regime isn’t even Vanuatu’s primary reason to forego income taxation. In an under-developed, under-banked, largely informal economy, where most citizens live off the land and don’t have electricity or modern plumbing, the cost of administering such a tax would far exceed the income it generated. Vanuatu’s government relies instead on VAT and various fees and licensing schemes.

The country’s revenue model is purely pragmatic and based on realistic assessments. Perhaps its leaders will one day find it relevant to enact income taxation, but not before the development gap is reduced between the capital of Port-Vila and the provinces, and the country’s infrastructure reaches a level of maturity that justifies big-government methods.

As long as Vanuatu adheres to global standards of fairness and transparency – and it does, as a signatory to treaties like the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard – the EU has no right to infringe on its sovereignty by dictating policies and tarnishing its global reputation and trade prospects.

Compounding Vanuatu’s trouble is its monetary sovereignty. Along with Fiji, Samoa and Trinidad and Tobago, it is one of only four countries in the EU Tax Blacklist that control their own national currency, and thus suffer significant consequences such a losing some of their correspondent banking facilities. The five remaining jurisdictions use the U.S. dollar as their currency and thus won’t lose any of their capacity for international transactions.

The elephant in the room

Perhaps any discussion about the EU Tax Blacklist should address the ambivalent position of French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna. Post Brexit, France has become the incarnation of Europe in the Pacific, and the only EU member with interests at stake there. The three overseas collectivities contribute 7 million km² to France’s enormous Exclusive Economic Zone and make it the last empire where the sun never sets.

As the world looks to the “blue economy” of the future, French policy makers are acutely aware of the growing importance of maritime resources such as fish, seabed minerals and deep-water oil and gas. Blindsided by Anglophone alliances in the region, and threatened by recurring independence movements, the French Republic has no choice, but to bestow every economic advantage on its territories while denying them to potential competitors. Hanging in the balance is France’s very relevance in the Pacific – and hence in the world.

The pot calling the kettle black

In addition to the EU Tax Blacklist, of which it is a key architect, France applies fiscal incentives in its three collectivities – just as if the rules dictated to their neighbours do not apply to them. There is no personal income tax in French Polynesia; there is absolutely no tax of any kind in Wallis and Futuna (not even a VAT like in Vanuatu); and there is no tax on personal capital gains in New Caledonia. One could argue that these “abusive tax practices” are robbing poorer Pacific nations of the foreign investment they so desperately need. Alas, the EU Tax Blacklist exclusively targets non-EU countries.

Despite all of its methodological hair-splitting, the EU Tax Blacklist is purely a farcical attempt by France to play global tax police in the eyes of its citizens, while clinging to its global relevance through a kind of neo-colonial behaviour that is becoming ever more obsolete.

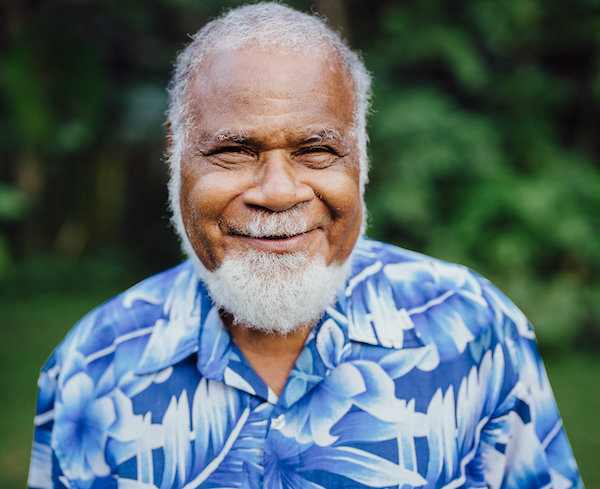

Sela Molisa was first elected as a Member of Parliament in 1983, representing the constituency of Espiritu Santo, his home island. He served in various ministerial portfolios, and has been Governor of the World Bank Group for Vanuatu, and a member of the Bank Group’s Board of Governors.