By Peter Judge

Throughout economic history, one of the key drivers of economic development has been cheap energy. It lowers production costs, increases productivity, stimulates investment, creates jobs, boosts competitiveness, and encourages consumption.

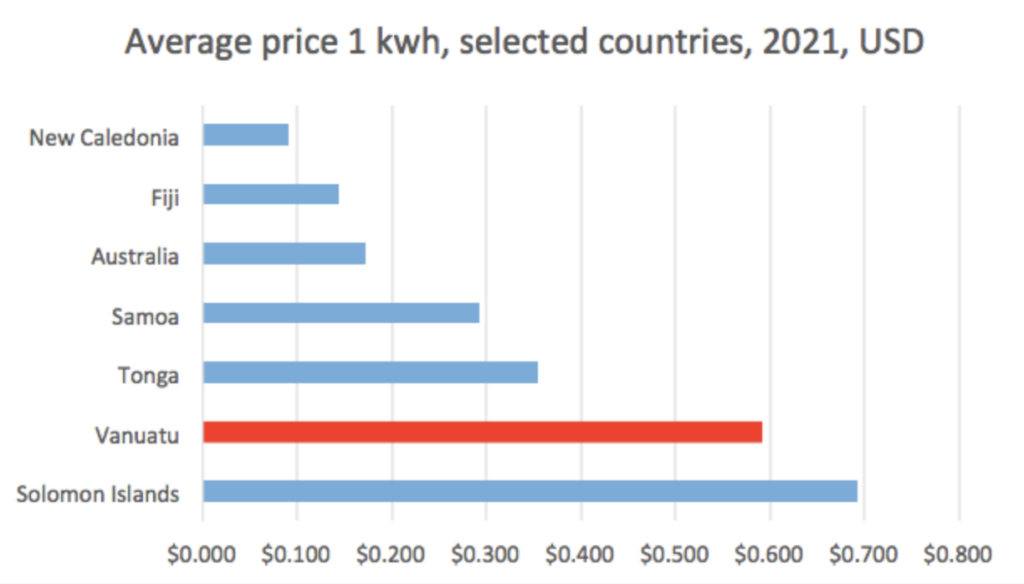

For Vanuatu, geography and technology have made historical energy prices high. Fossil fuels had to be used, and importing them was expensive. This is exacerbated by a lack of competition and the small-scale of the electricity grid, which means that the high fixed costs of building and maintaining the grid must be shared by a small number of customers.

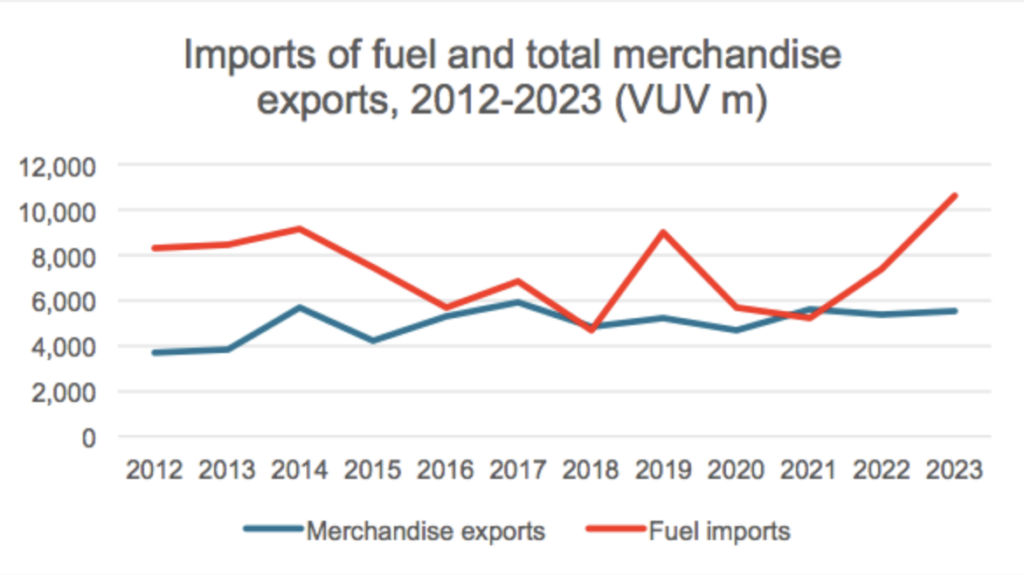

In the first 11 months of 2023 imports of fuel were 93% higher than total merchandise exports. This is a long-standing issue, and it is hard to imagine how any country could develop with such an imbalance. Reducing dependence on fossil fuels offers immense economic gain. And it is clearly possible.

The price of solar has fallen 99.6% since 1976, and 89% since 2009. It is now the cheapest form of energy and prices will continue to fall. Batteries are rapidly improving and getting cheaper.

Despite this, there has been minimal investment in solar or batteries. This is one of the reasons energy remains so expensive, with one research company estimating Vanuatu has the third most expensive average energy price in the world.

Renewable energy also has a different economic model with higher capital costs but lower operating costs. Who pays for the higher capital expenditure is a key question? If it is the energy companies, then this will mean it is ultimately the end-user who pays, limiting the benefits.

The system should therefore be designed so that as much of the capital expenditure as possible is done by others – Government, donors, businesses, and households – to have as clean and reliable energy as cheaply as possible.

Over the long run, growing energy demand from a growing population, continuous improvement in technology, and hopefully larger businesses and richer households will help the utility companies to develop economies of scale, and further reduce prices from the grid.

In the short-run, however, even if the transition to renewables is funded by grants then grid prices will not be able to drop by that much. This is due to other fixed costs (especially maintaining the grid and batteries) as well as challenges with load management and a need to maintain other capacity. But more renewable energy can provide stability in prices — a major gain given the geopolitical uncertainty while helping to set the grid up for the future.

It is a different story for businesses, whose lower fixed costs (they don’t need to build and maintain a grid), means they can see far larger reductions in energy costs if they install their own solar, while still being connected to the grid.

A number of businesses have done this. All interviewed were delighted by it and wanted to install more. The payoff time was generally between one and two years – essentially unheard of for Vanuatu.

At the moment however, investment is limited. Businesses in the Port Vila concession are limited to 30 kW of installed solar capacity, while in Santo they were unsure what the rules were. At a time when investment is so desperately needed, it is being stopped from happening.

The strongest argument for the current system is that Vanuatu’s energy grid is one of its most efficient sources of wealth redistribution wealth. Large consumers pay more to make energy very cheap for tiny consumers. If all of the restrictions are relaxed, then it would be the richest who would most easily be able to afford to switch away to renewables leaving the poorest with higher bills — an outcome which must be avoided.

An updated economic model is needed to ensure that businesses can unlock the immense potential of solar, whilst also ensuring the poorest have access to cheap energy.

This is where policy could recognise the difference between the sub-sectors. Manufacturing has been the engine of development for many countries and is the sub-sector most reliant on cheap energy. It provides employment, tax revenue, and demand for input products (such as fruit). It also reduces imports/boosts exports, increases resilience, and reduces exposure to imported inflation.

In Vanuatu, manufacturing’s contribution to GDP is just 2.2%, and its real value has fallen 27% since 2010.

Similarly, there are a number of primary sector businesses — such as poultry farms or aquaculture – which are vital and for who energy is a major cost.

The first idea is to allow primary sector and manufacturing businesses to install as much solar and battery capacity as they would like, while still being connected to the grid, and without facing any additional charges or higher prices. As the number of these businesses is small, the impact of this on the wider grid should be limited.

Any excess energy produced could be given back to the grid for free to acknowledge these businesses’ special treatment.

Other sub-sectors are more complicated. For hotels and resorts for example energy can be up to a third of operating costs. However, as they are major consumers, allowing them to go more self-dependent would have larger ramifications for the rest of the grid.

Innovative solutions should be thought of for how to make this work. One policy idea is that businesses or individuals can install as much solar as they like and still be connected to the grid, but in return they must supply a certain proportion back to the grid for free.

This has the advantages of unleashing investment from the private sector and individuals in a way that supports both themselves and the wider grid.

It would also increase resilience, by spreading production around as much as possible. Maintenance would be the responsibility of the owners of the solar, reducing the burden on the energy companies.

This would also likely involve the introduction of newer meters that can provide the required information to ensure everyone is following the rules.

This analysis of course mostly focuses on the main economic hubs. For smaller communities there are too many villages to rely on donors or the government to support them all. The best way to have widespread adoption is through either community projects or the private sector installing and managing micro-grids.

To make this happen there must be suitable products, finance mechanisms, skills, and waste disposal systems. These are all major challenges, but with suitable investment and plans put in place now, there would be a huge payoff for rural Vanuatu.

This is part of a series of articles by Peter Judge, Director of Economics and Research at Pacific Consulting Limited and author of the recent VCCI Private Sector Economic Outlook. The purpose of the series is to spark debate and further ideas, noting much more work is needed. All views expressed are solely his own.