By Ann Crotty

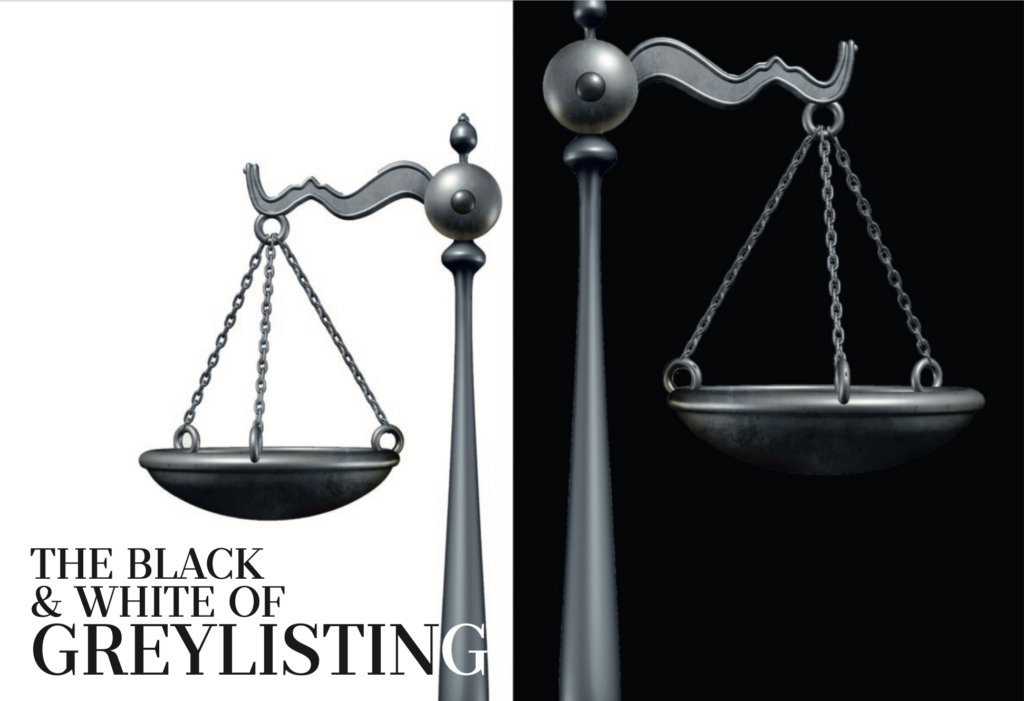

It’s time to call out the hypocrisy in the grey- and blacklisting of countries for financial crime and tax irregularities — larger countries that are regularly exposed fail to feature on such lists, which raises questions about their credibility.

One sure way of knowing if your country is a major player in the murky world of tax dodginess, money-laundering or the financing of terrorism, is whether it features on one or other of the lists drawn up by high-minded and righteous oversight bodies. If it is on a list, then chances are it’s not a player — or certainly not a major player.

There are lots of lists. There are greylists and blacklists. There are money-laundering and financing of terrorism lists and there are “uncooperative tax haven” lists. All are carefully curated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD), which specialises in tax matters; the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), focusing on anti-money-laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT); and, more recently, the EU.

Individual countries such as the UK, France and the Netherlands also have their own lists — which is hilarious, or perhaps disturbing, when you discover these are among the worst offenders.

The unfortunate countries that populate all these lists tend to be among the poorest, struggling to deve- lop in an increasingly hostile global environment. And, all too frequently, they’re former colonies of one or other major Western nation.

At present, the most consequential of the lists is the FATF’s AML and CFT list.

The FATF describes itself as an intergovernmental policymaking body whose purpose is to set global standards, and to develop and promote policies at national and international level to combat money-laundering and the financing of terrorism.

This is a commendable purpose, given all the dodgy money washing through the global financial system. As Koos Couvée, London-based reporter for the Association of Certified Anti-money Laundering Specialists, says: “There’s little doubt that naming and shaming has strengthened the global financial system by spurring nations to strengthen their AML rules and supervision, pursue cases against financial criminals and more thoroughly grasp their specific exposure to illicit finance.”

But there’s a catch. Between 2010 and 2020 the FATF grey- or blacklisted 65 jurisdictions, none of which is in the Group of Seven industrialised nations. And, so far, only two — Argentina and Turkey — are in the G20.

“The vast majority hail from the Global South and 28 rank in the bottom half of economic output as measured by GDP,” says Couvée.

The FATF blacklist is nuclear-level toxic and contains just three names: North Korea, Iran and Myanmar.

The current FATF greylist is considerably less toxic and, as of mid-February, contains 23 names, including Albania, Barbados, Burkina Faso, Cayman Islands, Gibraltar, Haiti, Mali and Yemen. This is the list South Africa might be joining at the end of the month, unless it can somehow persuade the FATF’s rather shadowy International Co-operation Review Group that it has made sufficient progress in bringing its legislation and capacity in line with FATF requirements.

Evidently the FATF committee was not swayed by the fact that Xolisile Khanyile, head of South Africa’s Financial Intelligence Centre, received the Financial Crime Fighter Award for 2022 — essentially the global financial crime fighters’ Oscar. Nor was it persuaded by the recent passing of important legislation, or the significant increase in corruption-related prosecutions.

It seems, as Corruption Watch’s former executive director David Lewis says, that more people have to actually end up behind bars — which is reasonable enough.

But whatever frustration South Africans might feel about being tacked onto the list of underperformers, think how it must feel to be one of the smallest and poorest countries in the world and feature almost constantly on one or other of these lists.

South Africa is, after all, one of the 38 member countries of the FATF, and it has sufficient political heft to be listened to. Not so much the likes of Panama, Trinidad & Tobago, Vanuatu, Barbados, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Bahamas, South Sudan, Senegal, Samoa, Zimbabwe or any of the other 50 or so countries that spend their already pre- carious lives on a list or being considered for a list.

Barbados-based economist Marla Dukharan was fairly phlegmatic about it all until the EU decided to get in on the act. The EU lists are not only arbitrary and farcical, Dukharan tells the FM — they’re racist.

While she quickly acknowledges the importance of oversight of global financial flows, Dukharan is also heartily sick of the prevailing narrative that tropical islands are the worst tax havens in the world.

That not one of the major players that are regularly exposed in independent research ever features — think the UK, the US, Ireland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore or Luxembourg — raises questions about the credibility and motives of those behind the lists.

“If the OECD and EU are interested in addressing illicit financial flows, they should start with their own members where financial crime thrives, based on abundant evidence,” says Dukharan.

Some of that evidence comes from no less a source than the UK’s own parliament. A recent report by its foreign affairs committee referred to London’s reputation as a hub for illicit finance. It went on to note that by the government’s own measure, “there is a realistic possibility that the scale of money-laundering impacting the UK annually is hundreds of billions of pounds [which is] washed clean until it is to all intents and purposes now apparently legitimate”.

As for tax concerns, well, according to Tax Justice Network, OECD members are responsible for more than two-thirds of the world’s corporate tax abuse. And members of the EU parliament have confirmed that EU countries account for 36% of the world’s tax havens. You certainly wouldn’t guess that from looking at the names on the grey- and blacklists.

The countries on the EU grey- and blacklists account for less than 2% of worldwide tax revenue losses and a mere 1.1% of global economic activity.

Whatever way you look at it, it’s difficult to imagine how these countries, even if they were co-ordinated in their supposedly dastardly machinations — which they decidedly aren’t — could represent the slightest threat to the global financial and tax system.

As a nod to reality, the EU has included China and the US on a priority list for assessment, but so far has avoided their inclusion on an actual list.

As lawyer and certified AML and global sanctions specialist Andrew Dalip suggests, this is likely explained by the scale of their economies and the potential impact on the EU financial system. To the naive this sounds like reason enough to be slapped on a list rather than excluded. Still, given that the US has managed to ensure it is permanently excluded from the OECD list through deft rewriting of the rules, the chances of it ever ending up on an EU list are remote.

Dukharan is rightly incensed by the racist bullying that underpins the EU’s processes which, she says, comes at significant cost to the victims.

“Not only is there reputational damage, but listing inevitably leads to financial institutions in Europe and North America withdrawing or reducing their correspondent banking services, which increases the cost of banking for the targeted countries,” she says. There’s also an exponential increase in paperwork.

And it seems, judging by the treatment meted out to Barbados, there is little reward for trying to keep up with the EU’s ever-changing requirements.

Tax Justice Network CEO Alex Cobham warns of the growing concerns around the legitimacy of listing processes, which frequently involve former colonial powers dictating to former colonies.

“The OECD, FATF and EU are setting global rules and forcing them on countries that are not members of these exclusive organisations,” Cobham tells the FM.

At the same time, he welcomes recent signs that the UN is moving on the issue. “The UN was established to deal with countries with competing interests, it operates in a more transparent, accountable and inclusive manner, which will ensure its decisions are more effective and legitimate,” he says. A recent shocking ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) reinforces Cobham’s belief that these powerful global organisations are little more than the tools of powerful business interests.

Last November the ECJ declared invalid the section of the EU’s 2018 anti-money-laundering rules that allowed public access to registries detailing companies’ beneficial owners. As the Financial Times wrote, that public access had helped expose myriad alleged abuses, including by the Czech prime minister and a Lebanese central bank governor. Transparency campaigners described the decision, in the case brought by a Luxembourg-based businessman, as likely to have drastic effects on efforts to tackle money-laundering and the abuse of shell companies.

Of course, the point might be made that, given that these powerful countries control so much of the world’s finances, they are best placed to set the rules. That’s reasonable enough — but it’s not an oversight principle that has been adopted in dealing with an equally fraught global challenge: climate change.

The UN’s Conference of the Parties (COP) may work rather ponderously, but it has the legitimacy as well as the crucial buy-in from members of the UN that’s needed to make any progress.

Nobody would attempt to argue that, as representatives of the dominant producers of carbon emissions, the OECD, FATF and EU should run the world’s climate-change programme. If they did so in the same way they run the tax, AML and CFT processes, it’s likely they would be scouring the “developing” world for small-scale industries that could be shut down while leaving their own mega-carbon-pumping industries untouched.

It really is time for the financial police of the world to decide whether they’re going to take this issue seriously and take on the major players.