By Martin St-Hilaire, Chairman of the FCA

Released on October 3rd, the Pandora Papers revealed to the world how the rich and powerful shelter huge amounts of money from tax in places ranging from the British Virgin Islands to South Dakota. Two days later, the European Union announced a new list of “harmful” tax havens that includes Vanuatu and almost none of the jurisdictions singled out in the Papers.

This begs the question: what planet are the EU officials on?

Launched in 2017 and updated twice a year ever since, the EU’s list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes (a.k.a. the Tax List) is a curious mix of places who share the distinction of having low or no income tax, and of also being poor, defenseless, and not related or allied with an EU member state.

According to the latest Tax List update, the most unfair fiscal policies on the planet are currently found in nine jurisdictions: American Samoa, Fiji, Guam, Palau, Panama, Samoa, Trinidad & Tobago, US Virgin Islands and Vanuatu. We are supposed to believe that this gang, through their “abusive tax practices”, pose a grave threat to the public revenue of EU member states.

Any way you look at it, the Tax List is just preposterous.

For starters, the discrepancy in scale is downright shocking. While an estimated $21,000 to $32,000 billion is held in global tax havens, the combined GDP of the Gang of Nine is only $92 billion ($13 billion if you count only those in the Pacific), or about 0.1% of the world economy.

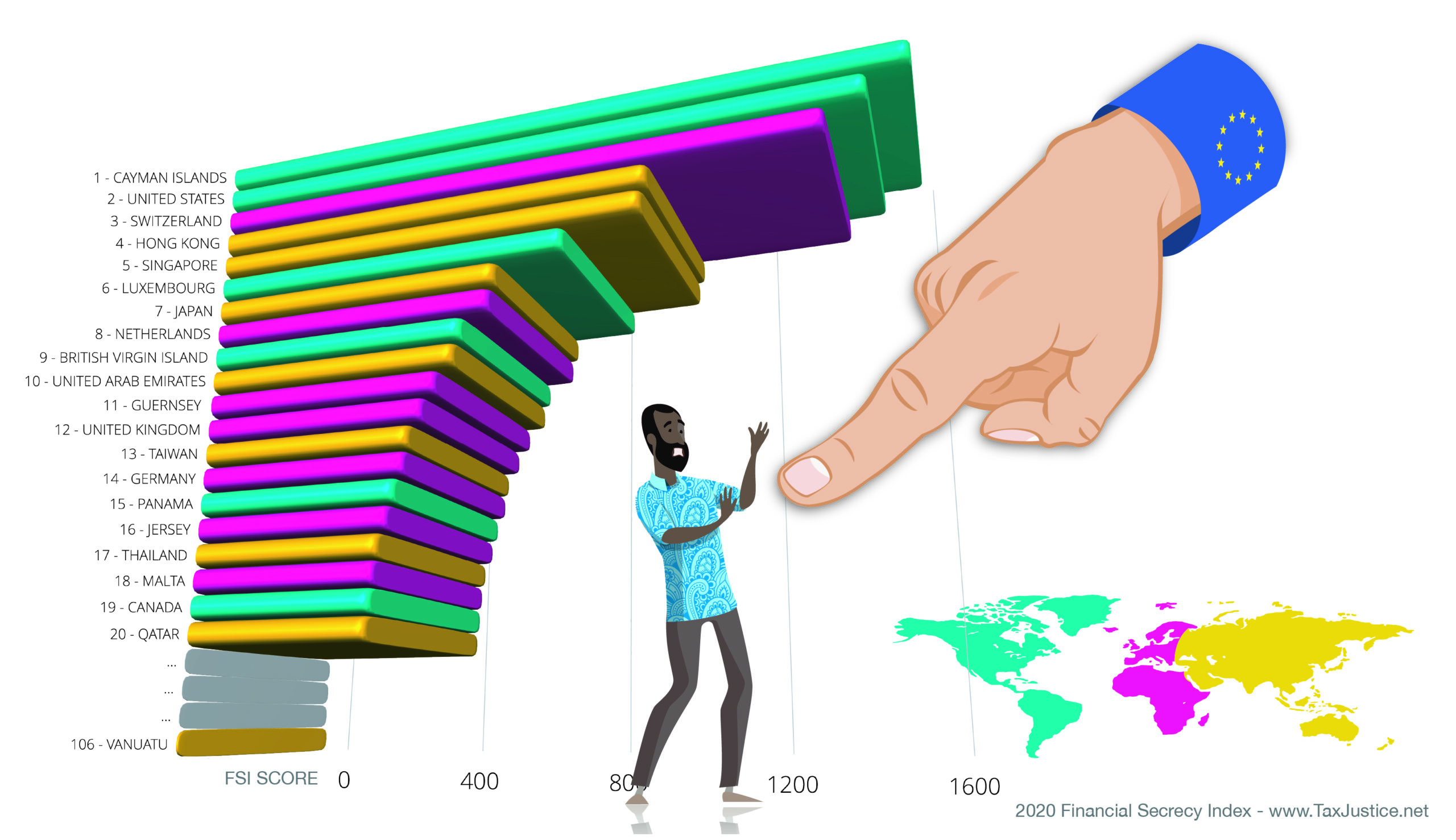

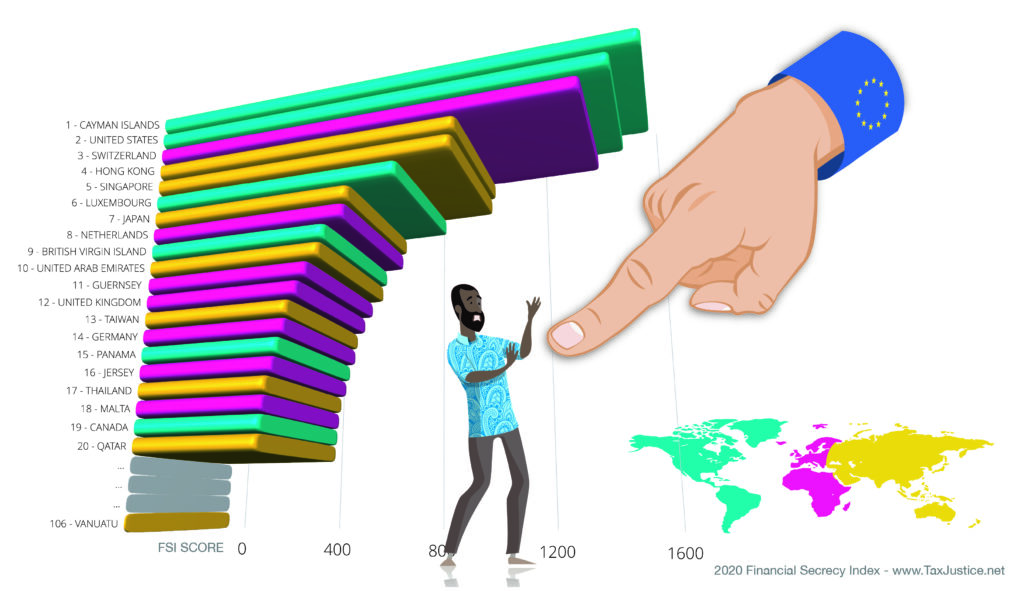

We are so insignificant that Vanuatu is ranked only 106th on the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). Despite all of our alleged harmfulness, we only account for 0.0008% or a flyspeck of the global offshore financial services market. Even if all of that money was sheltered from European tax collectors (which it isn’t), Vanuatu should be rock bottom on their list of worries. Instead, it’s at the very top, up there with mighty Fiji and Palau.

What doesn’t seem to concern them are actual tax havens. According to the FSI, the 10 biggest concealers of private money are the Cayman Islands, the U.S., Switzerland, Hong Kong, Singapore, Luxembourg, Japan, the Netherlands, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) and the United Arab Emirates. (They don’t necessarily act as tax havens for their own residents but can provide fiscal loopholes for foreign citizens). These are the world champions of offshore tax evasion, and at a level that far eclipses

that of Vanuatu and its unfortunate brethren. Yet they don’t show up on the Tax List – except for six-month stints by the Cayman Islands and the UAE. For so many EU members and their allies, their biggest talent after tax evasion seems to be list evasion.

The absurdity of the Tax List was only compounded by the release of the Pandora Papers, a trove of 12 million confidential files leaked from 14 offshore services firms. Led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), involving more than 600 journalists from 150 media outlets in 117 countries, the project exposed the secret stashes of more than 130 billionaires and 330 politicians and public figures from 90 countries and territories.

Their assets ended up in a variety of places, from the BVI to South Dakota and other U.S. states where legislators have introduced loopholes in recent years to attract these lucrative investments. Not a cent ended up in Tax List jurisdictions. (One exception is Samoa, whose financial regulator pointed out in response that the key levers of its offshore industry are in much bigger countries such as Singapore and the UK.)

To anyone reading the news, the EU list looks more disconnected than ever from reality. But to be fair, it’s not that Brussels bureaucrats don’t know where the actual tax evasion takes place; it’s just that those places don’t fit the criteria of the Tax List. You see, the methodology of the Tax List is concocted in a way that filters out the actual tax havens with powerful connections, and singles out the would-be tax havens with no way to defend themselves. In each iteration since 2017, its purportedly rigorous criteria have produced more or less the same result. The end goal was never to name and shame active fiscal competitors, but to prevent new ones from emerging and eating the others’ profits.

Case in point: the Bahamas, which in 2018 enacted legislation requiring certain structures to declare their owners to a government registry, was removed from the Tax List as a reward and, as a result, lost sizeable business to American states which do not have such laws. As reported by the ICIJ, the family of the Dominican Republic’s former Vice President Carlos Morales Troncoso abandoned the Bahamas to store its wealth 2600 km away in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “The winners of these new double standards are the U.S. states of Delaware, Alaska and South Dakota,” one Bahamas attorney is quoted saying.

The Bahamas story not only hints strongly at the EU’s aim of taking down would-be fiscal rivals rather than established tax havens, it also serves as a cautionary tale for Vanuatu. If we comply with everything the EU asks, we will deprive ourselves of one of the only tools at our disposal to attract foreign investment and grow our economy: our business-friendly tax regime and offshore financial centre.

While Western democracies let all kinds of shady customers hide their wealth on their soil, all we’ll ever get from acquiescing to every EU fiscal demand will be stagnation or worse. We’ll remain stuck with our hopelessly limited resources, and forever dependent on foreign aid. We’ll still have the much-needed extra income from our citizenship program – wait, the EU wants us to drop that too!

The EU Tax List is blatant hypocrisy and nothing less. Every time European bureaucrats try to teach us how to enact sound policy, let’s remember whose interests they have at heart. Sure, Vanuatu is far from perfect; it’s still a young nation that needs to fine-tune how it operates before it can further develop. But the last thing our economy needs is to be held in a chokehold by the EU, especially on such specious grounds.