By Stephen Howes and Sherman Surandiran

Economic data out of Vanuatu indicates that the country’s economy has been less affected than expected by the COVID-19 pandemic. No doubt there has been real economic pain. But the latest GDP figures show a fall of only 2.1%, much less than the 10% the ADB had earlier predicted. This comes as a surprise given the country’s dependence on tourism, but also calls into question the extent of that dependence.

Agriculture, fishing and forestry also suffered in 2020 from Cyclone Harold, but kava is a bright spot with an estimated 5% growth. To quote from Vanuatu’s 2021 budget: “As kava prices gradually appreciate in value relative to other commodities, combined with the prospect of kava being accepted to the European market as a beverage, production is expected to be scaled up over the medium term.”

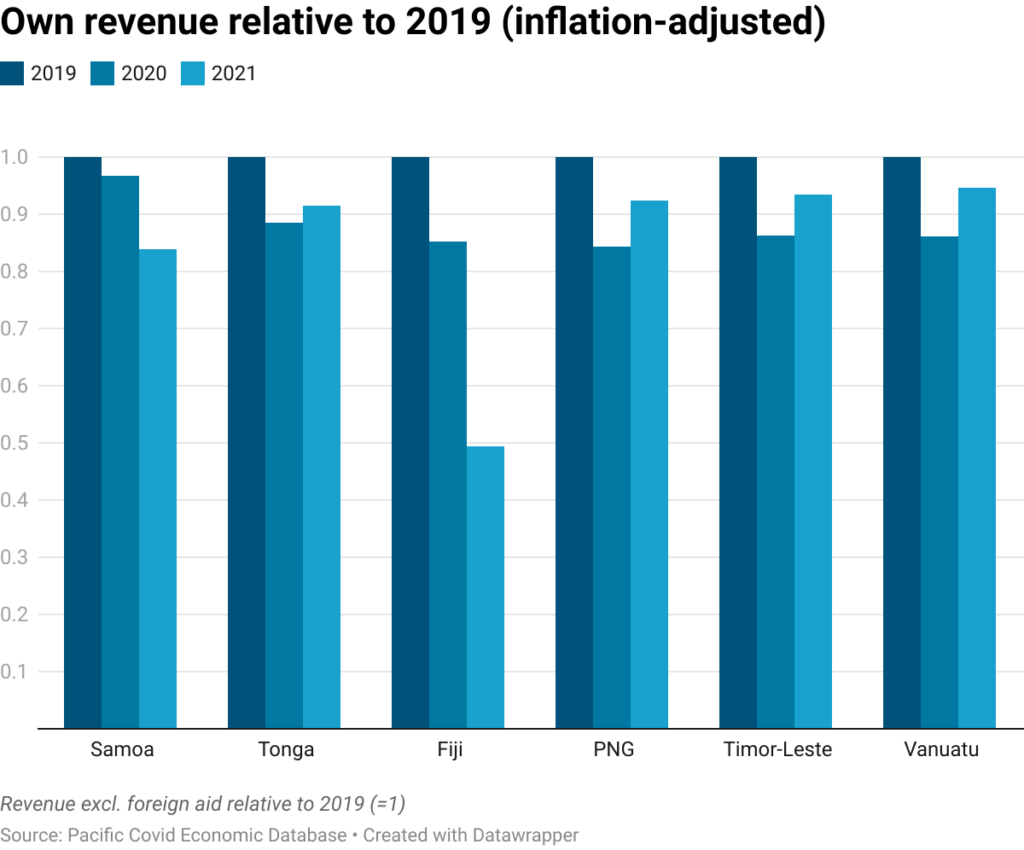

Revenue has taken a bigger hit than GDP. The predicted inflation-adjusted drop in government revenue (excluding aid) is 14% compared to 2019 levels, due to the reduction in tourism and resultant job losses. (All data from our updated COVID-19 economic response database.)

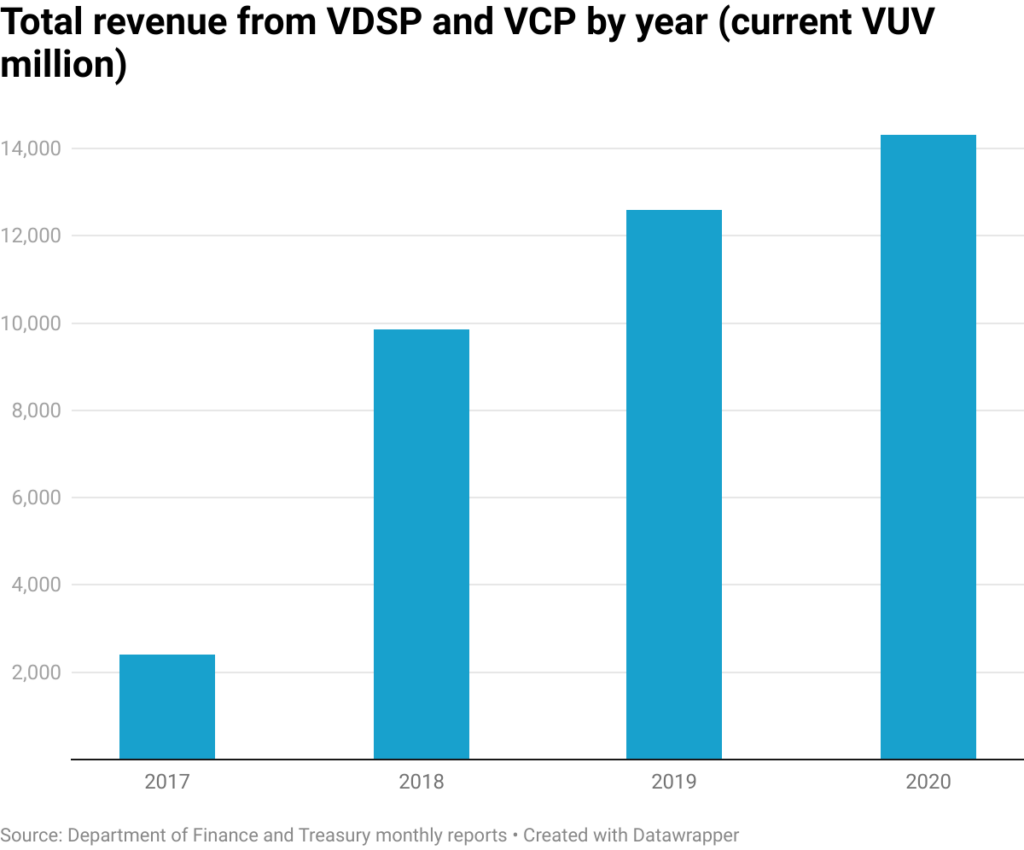

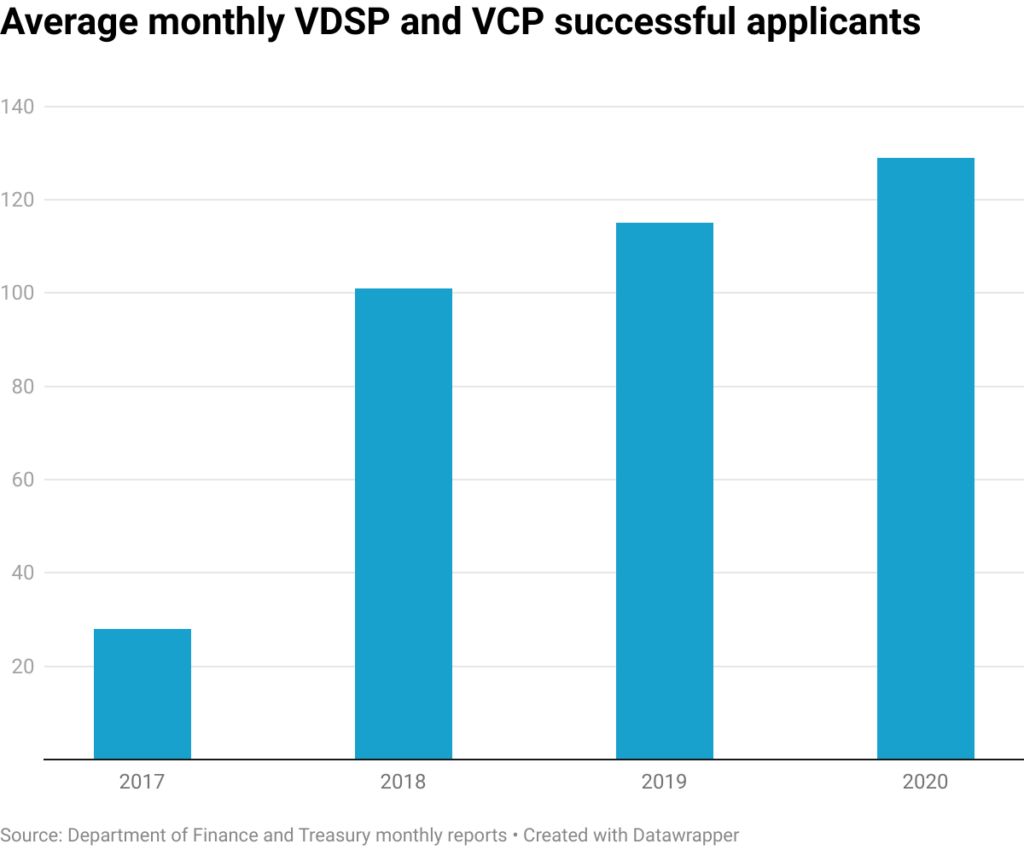

But here too there is good news. Say what you want about Vanuatu’s citizenship-for-sale schemes, but they are certainly lucrative, and continue to grow. Here we update our analysis from last year of the Vanuatu Development Support Program (VDSP) and Vanuatu Contribution Program (VCP). In 2020, Vanuatu had more applications into its schemes, and made more money from them than ever. The two citizenship schemes are now responsible for 35% of total government revenue, up from 29% in 2019, 25% in 2018, and just 7% in 2017. Clearly the schemes are COVID-proof. After all, you don’t need to actually visit Vanuatu to get a passport.

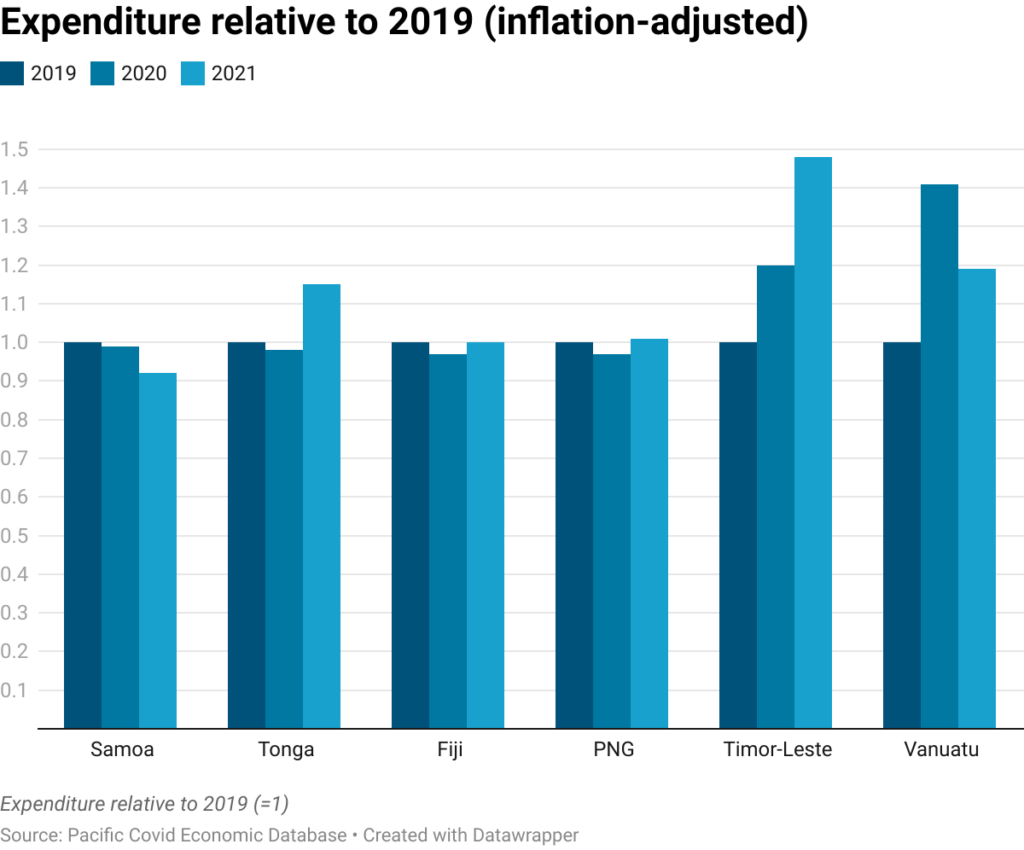

Compared to other Pacific countries, Vanuatu did well in 2020 to increase expenditure in response to COVID-19, with increased spending on subsidies and goods and services.

Anyone arguing that Vanuatu should dump its citizenship schemes should have a good look at the above figure. The only two countries shown in the graph able to mount a serious fiscal response to COVID-19 have been ones with fiscal buffers: Timor-Leste has a sovereign wealth fund with oil earnings, and Vanuatu has its citizenship proceeds.

Vanuatu ran a deficit in 2020 due to the pandemic. But after years of large surpluses(again thanks to those citizenship schemes), its debt position remains comfortable, and the country has declined to participate in the international Debt Service Suspension Initiative.

There are two dark clouds. One is the country’s low vaccination rate. As of the end of July, only 7,000 vaccines have been administered, which is about 7% of the population. Vanuatu has kept COVID-19 out of the country so far, but with more infectious strains around, for how long will that be possible? Even if Vanuatu does keep COVID-19 at bay, the opening of international borders looks ever further away, at least in this part of the world.

Vanuatu’s second big risk is international financial isolation. In March, the National Bank of Vanuatu put out a statement to the effect that, since the National Australia Bank (NAB) had decided to end its correspondent banking relationship with it, no new USD accounts could be opened, and it might not be possible to provide USD to its clients in the future. The decline in correspondent banking relationships is a Pacific-wide phenomenon, and NAB has withdrawn from the Pacific completely. But some argue that this decision was linked to concerns about the citizenship-for-sale schemes (which are paid for in USD). Whether it is or not, it is clearly a negative development, and the IMF last month specifically warned that “revenues could fall sharply amid growing concerns on AML/CFT [regulatory] risks” to Vanuatu’s citizenship programs.

So, some serious challenges ahead but, in what has been a gloomy period, Vanuatu’s recent economic performance is definitely good news.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University. Sherman Surandiran was a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre until July 2021. This research was undertaken with support from the Pacific Research Program, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are those of the authors only.