Don’t feel bad if you’ve never heard of my country. Vanuatu is very small, poor and low-key – a sprinkling of 83 islands in the Southwest Pacific with just over 300,000 souls, most of whom don’t have electricity or improved sanitation. We’re a peaceful bunch and we don’t make much noise on the global stage. Still, for many years we’ve been receiving a disproportionate amount of attention from the European Commission – with devastating effects on our economy.

Europeans have been around Vanuatu for a very long time. The Spaniards, the French and the English came and went, including James Cook who named the place the New Hebrides. It was later run as an Anglo-French condominium (a fancy name for a colony under joint custody) from 1906 through 1980, when the founding fathers of our Republic finally declared independence and gave it its current name.

Ever since, Vanuatu has remained dependent on foreign aid to survive. Most of it has been provided by our former masters, the U.K. and France, along with Australia, New Zealand and various multilateral organizations.

The European Union offers bilateral aid to our government – to the tune of 25M euros in direct budgetary support for the latest cycle (2014-2020) – along with aid programs for the broader Pacific region. At the COP26 summit last year it launched the BlueGreen Alliance, a financial framework for the Pacific focusing on climate change, sustainable development, human rights, and security.

These are all very good deeds. Our nation recognizes that European generosity has been instrumental in keeping us afloat through difficult challenges, and we share many of the values promoted in the process.

However, we would feel much more grateful if Europeans didn’t simultaneously use their wealth and influence to constantly undermine our economic growth.

Keeping our economy on a tight leash

Financial aid is the carrot; now comes the stick. Vanuatu has the dubious distinction of appearing on not only one, but two European blacklists: one regarding tax evasion (I’ve written about it here), and the other, money laundering and the financing of terrorism (read my other piece here) .

The globally recognized authorities in these matters – the OECD for the former and the FATF for the latter – have long declared Vanuatu compliant with their standards. The European Commission is alone in its insistence that we are dangerous facilitators of financial crime.

For many years these blacklists have been undeserved stains on our country’s reputation, with direct economic damages since they tend to turn off potential trading partners and investors, at a time when we badly need to diversify our economy.

Our current GDP is under $900M. Most of our population still lives off subsistence agriculture. While foreign aid has long been helpful in providing our people with basic necessities, including infrastructure, healthcare and education, depending on the largesse of others is not sustainable in the long term. We need to grow our economy on our own by developing our export industries – especially since COVID has robbed us of tourism.

We still don’t know why

The EU blacklists make this goal harder to reach. They have little effect on tax evasion, money laundering or the financing of terrorism, but they do give us a debilitating handicap in the global competition for capital investment.

If we were such hardened enablers of financial crime, you would think the European Commission would be eager to resolve the issue by demanding specific actions on our part. Think again. Our leaders and diplomats have been pressing them for answers for years, only to be met with silence, delays, and vague promises of reassessments that somehow never come.

We play by the rules, we adhere to global standards, but the EU blacklists unfairly keep our economy on a leash. After 42 years of independence, we have yet to achieve autonomy. We are a sovereign people, yet our welfare still hangs on the whims of Europeans.

The French elephant in the room

Perhaps I am being unfair in my broad statements about Europeans. They might very well apply exclusively to the French.

Vanuatu may be far from continental Europe, but it is very close to the French territory of New Caledonia, whose native population shares our Melanesian heritage. Our people have been living together for millennia, and many of us have friends and relatives there. But politically, it’s another world.

Along with French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia is a vivid reminder of the history of French colonialism in the Pacific. In fact, while they are officially named “overseas territories”, one could argue that they have retained many of the defining features of colonies, only under a more innocuous name.

In fact, under longstanding decolonization principles, the UN General Assembly refers to French possessions in the Pacific as “non-self-governing territories” (NSGT), “whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government” according to chapter XI of the UN Charter. Although successive generations of French diplomats have resented this pursuit of self-government, many of their indigenous subjects have been calling for independence.

One good way to quell this kind of revolutionary fervour is to point to the abject failure of the independent ex-colony of Vanuatu, as President Macron did in his July 2021 speech from Tahiti. Drawing from Homer’s Odyssey, he warned against heeding “the siren’s call” of “adventurous projects” with “uncertain financing” and “strange investors”. “I look at what happened in the region, in Vanuatu and elsewhere (…) My friends, let’s hang on to the mast”, Macron urged, pointing to the value of the “protection” offered by France to its territories.

For sure, securing sound financing is key to ensuring the prosperity and well-being of my people. If only there wasn’t a European bureaucracy hell bent on undermining our prospects for international trade and economic growth.

The benefit of the doubt

It’s easy to be cynical and think that France is making an example of Vanuatu to dampen the fervour for independence in its territories, or to rather cruelly clip the wings of an economic competitor in the region. But I prefer to believe in the good intentions of the French, and that they simply do not realize how much harm their economic roadblocks cause.

It seems the historical champions of human rights have simply failed to grasp that the preservation of our rights and freedoms simply outweighs any economic ambitions they may have in the region.

It’s interesting to note that the British, whom we remember to have been much more supportive of our independence back in 1980, have not included Vanuatu on their own money laundering blacklistafter they left the European Union. The inclination to bully Vanuatu appears to be stronger in France.

We may not enjoy its “protection” like its territories do, but could we at least be left alone?

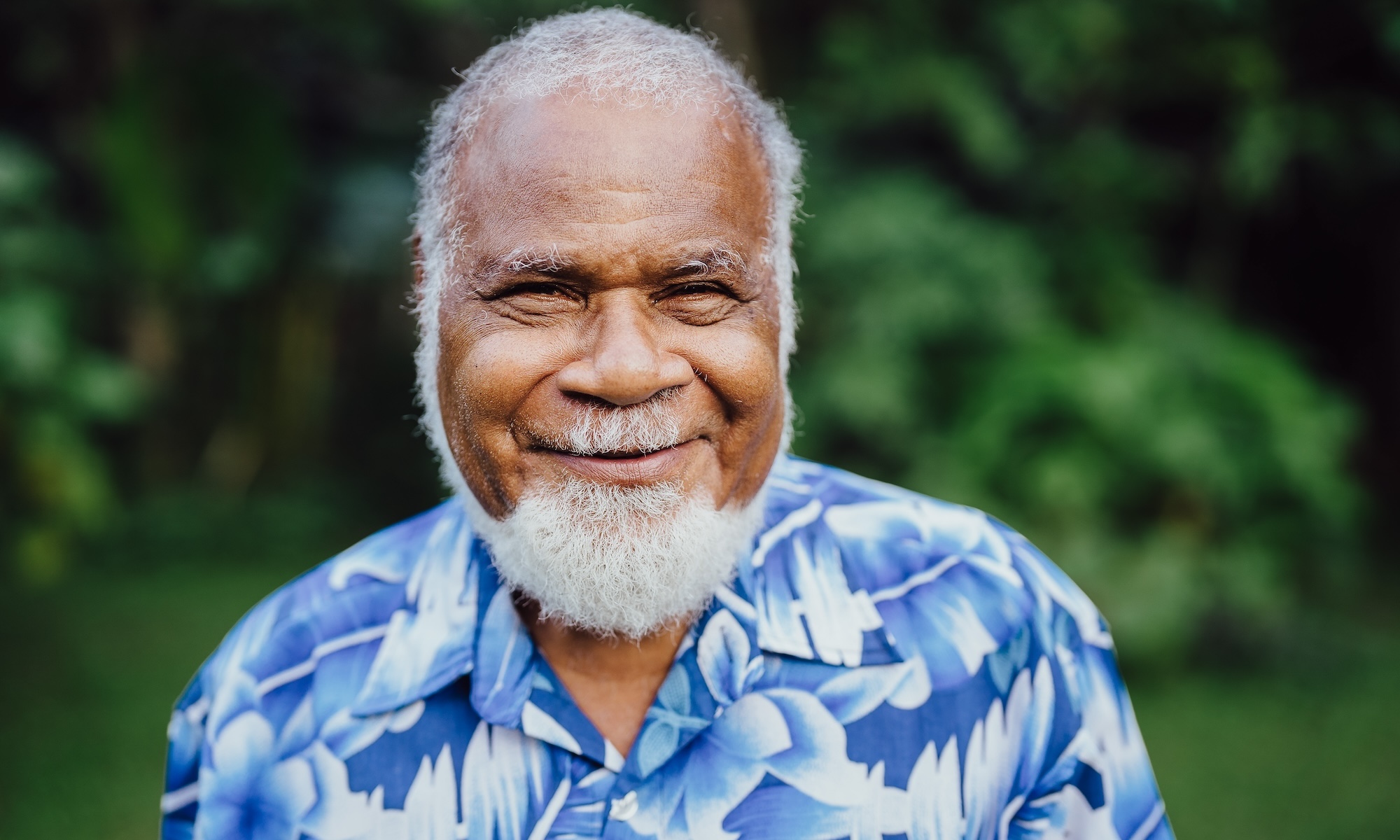

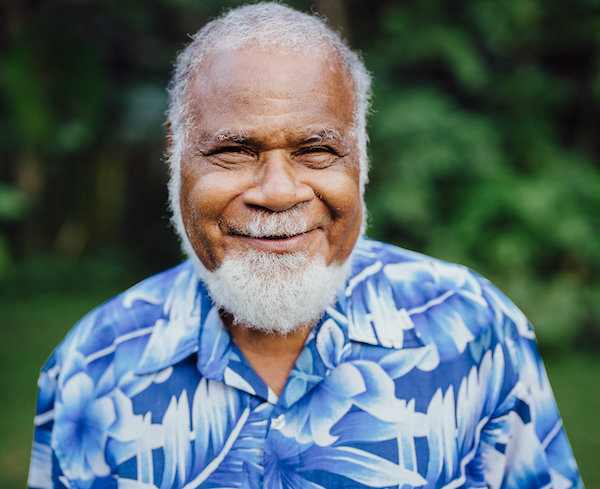

Sela Molisa was first elected as a Member of Parliament in 1983, representing the constituency of Espiritu Santo, his home island. He served in various ministerial portfolios, and has been Governor of the World Bank Group for Vanuatu, and a member of the Bank Group’s Board of Governors.