By Sela Molisa

In its six years of existence, the EU list of “high-risk third countries” hasn’t done much beyond parroting the work of established money laundering watchdogs – except for a few, seemingly deliberate departures. Some of these blacklistings are doing real damage.

While the general public may not know much about the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it is the single most important institution in the world in the fight against money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (or AML/CFT).

Established in 1989 by the G7 and housed at the OECD in Paris, the FATF comprises 37 member countries, 2 member organizations (one of which is the EU), and countless associate members and observer organizations. Charged with defining minimal requirements and promoting best practices in AML/CFT for global markets, the FATF maintains two watchlists of jurisdictions that fail to meet those standards, classified either as “high risk” or “under increased monitoring”. Most financial institutions in the world rely on these lists for their compliance checks, from local banks and payment providers all the way up to the BIS, the IMF and the World Bank. Additions and withdrawals from these lists are decided after thorough and intensive mutual assessments, and carry major consequences for the international trade prospects and economic outlook of targeted jurisdictions.

Madness in the method

While the FATF is inarguably doing a fine job of policing financial markets, in 2016 the European Commission decided to run its own, separate list of “high-risk third countries” for AML/CFT purposes. At first it was an exact copy of the FATF lists; the Commission then introduced its own methodology in 2018, which was revised in 2020 as a “two-tiered approach” with “eight building blocks”, ensuring robust, objective and transparent scrutiny. As high-minded as this sounds, the resulting list continues to remain consistently similar to FATF findings, as it has over the years – with a few notable exceptions.

In its current iteration (January 2022), the European list includes 25 jurisdictions, just like the current FATF lists (March 2022). Only four names appear on the EU list but not on the FATF list – Afghanistan, Trinidad & Tobago, Vanuatu and Zimbabwe – and four others are absent from the EU list – Albania, Malta, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

While the FATF documents every listing and delisting with utmost clarity, the same cannot be said for the European Commission. Anyone trying to understand its rationale for these eight exceptions runs into a maze of byzantine verbiage that never quite leads to any real understanding. The reasoning is online for everyone to see, but even the most seasoned technocrat would be flummoxed trying to deciphering it.

The curious case of Vanuatu

Let’s look at the case of Vanuatu, a tiny, poor island nation of 300,000 sprinkled between Fiji, New Caledonia and the Salomon Islands. During an FATF-mandated assessment in 2015, it appeared that the country was falling short in its AML/CFT commitments, and while no incident had been reported as of that time, the FATF cautiously listed Vanuatu as “under increased monitoring”.

As an underdeveloped country, Vanuatu has many pressing priorities, starting with the urgent need to develop proper infrastructure, healthcare and education, and it was recovering that year from the extremely destructive Cyclone Pam. But its leaders knew that an FATF listing is no small matter, and the government rallied along with the financial industry and undertook an ambitious legislative overhaul that created new institutions charged with enforcing stricter AML-CFT controls. Upon inspection on site, the FATF was satisfied and delisted Vanuatu in June 2018.

This was around the same time the European Commission adopted its own AML/CFT blacklisting methodology, and while every single financial institution in the world took notice of the FATF decision, Brussels did not – and Vanuatu has been marooned on the EU list to this day.

Bureaucratic opacity

As thorough as it may be, the European methodology that kept Vanuatu blacklisted did not include any direct assessment or any request for information; it was a unilateral process that took place in a vacuum, entirely in a Brussels office, without any communication with the country’s leaders. Only in mid-2020 did the Commission finally submit a breakdown of prerequisites for Vanuatu to be removed from the list; but the document was weighed down with erroneous statements and, when pressed for answers, the bureaucrats dragged their feet another year and half before sending a second, even more confusingjumble of confounding recommendations.

To this day, the process that would see to Vanuatu’s removal from the European high-risk country list remains elusive. Four years have passed since the FATF and most global institutions deemed the country compliant, but Brussels still refuses to concur and gives little explanation as to why.

Vanuatu is not the only victim of the Commission’s mysterious ways. Iraq once shared the same fate – delisted by the FATF in the same 2018 decision, but kept on the EU blacklist anyway – until it finally got the all-clear in January. Two months later came an “Oops!” moment for the Commission, when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists revealed how telecom giant Ericsson paid protection money to move equipment through ISIS-held territory. Meanwhile, no instance of terrorism financing has ever been reported in Vanuatu, nor any money laundering for that matter.

The perfect scapegoat

Vanuatu is a young country – it declared independence from Britain and France just 42 years ago – and just recently graduated from Least Developed status. The next logical step in its development would be to diversify its economy and grow its meagre GDP (currently under $1B) by taking part in global trade and attracting foreign investors. As long as the EU insists on misinforming foreign investors and correspondent banks that Vanuatu is a haven for money launderers and terrorists, it’s effectively holding it back from achieving these goals – still with no clear path to delisting after four long years.

Brussels can discriminate against Vanuatu as long as it desires because the small country is the perfect scapegoat; it doesn’t retaliate, doesn’t have allies and doesn’t hire lobbyists. It’s a peaceful nation that suffers in silence. But European taxpayers would be wise to ask their bureaucrats to demonstrate how exactly their high-risk third country list is not an exercise in pure futility and waste – with only harmful impacts on poor countries.

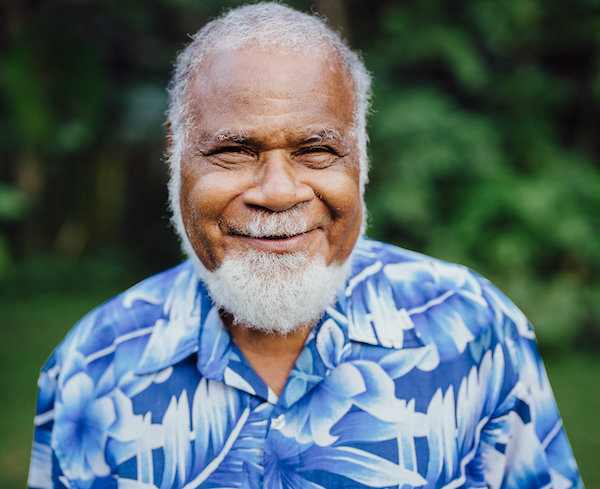

Sela Molisa was first elected as a Member of Parliament in 1983, representing the constituency of Espiritu Santo, his home island. He served in various ministerial portfolios, and has been Governor of the World Bank Group for Vanuatu, and a member of the Bank Group’s Board of Governors.