By Sela Molisa

The European Commission insists that the biggest tax havens on the planet are a sprinkling of small tropical nations in the Pacific and Caribbean that comprise less than 1% of living humans and produce under 0.1% of global GDP. Meanwhile, actual tax havens go unpunished. Is Brussels really chasing tax evaders or just looking for scapegoats?

Twice a year, in October and February, the European Commission updates the “EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes” (a.k.a. “the tax blacklist”), whose purported goal is to “protect [European] tax revenues, and fight against tax fraud, evasion and abuse”. The two most recent iterations have remained unchanged, at nine names:

- American Samoa (population 55,200)

- Fiji (896,400)

- Guam (168,800)

- Palau (18,100)

- Panama (4,315,000, by far the largest on the list)

- Samoa (198,400)

- Trinidad and Tobago (1,399,000)

- US Virgin Islands (106,300)

- Vanuatu (307,000)

European readers may be forgiven for not being familiar with some of these names, as they sit half a world away and are but specks in the global economy. Nevertheless, the public is expected to believe that this is an exhaustive and definitive list of the most desirable destinations for European tax evaders.

Where are the actual tax havens?

Since its inception in 2016, the EU tax blacklist never came close to including the British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Jersey, the U.A.E. or any of the other notorious and widely documented tax havens in the world. Most names appearing on the blacklist over the years were among the smallest players (Bahrain, Belize, Morocco, Namibia, Seychelles…) whose impact on the global economy and the public revenues of European states is negligible.

In fact, with the exception of Panama, none of the nine jurisdictions currently blacklisted by the Commission are listed among the Tax Justice Network’s Top 70 corporate tax havens, a far more authoritative list on the matter.

One can also look to the Pandora Papers or the recent Credit Suisse scandal to shed some light on tax evasion taking place around the world, from Delaware to Switzerland; Brussels’ Gang of Nine is nowhere to be found here either.

Among other prominent tax transparency advocates criticizing the EU tax blacklist, Oxfam recently pointed out that it should “penalise tax havens, not punish poor countries”. To no avail – twice a year, like clockwork, the Commission keeps on churning out the most unexpected names, all of them false positives.

Only small and voiceless nations come under scrutiny

This begs the question: How does the European Commission consistently come up with such an idiosyncratic list of tax havens? There is an official process, organized around the three main criteria of tax transparency, fair taxation, and the implementation of measures against base erosion and profit shifting (“anti-BEPS”) – which are reasonable expectations when fighting tax evasion.

But there is another, crucial criteria that supersedes the others: Only third countries are to be assessed, meaning EU members are automatically excluded. What’s more, upon closer inspection the process almost never considers any dependency of an EU member (like the French territories of French Polynesia and St-Martin, despite their generous tax regimes) or ex-members (such as U.K. overseas territories, many of which rank high on the Tax Justice Network’s list).

Whatever rigour is applied in the process, it consistently produces a list of the smallest, most inconsequential economies on the world stage that typically lack powerful allies and are therefore virtually voiceless in Western capitals and the European Parliament.

Grandstanding for taxpayers

The Commission would certainly face a backlash if it publicly challenged the fiscal policies of the large and powerful tax havens where EU citizens actually shelter their wealth, from the Cayman Islands to Singapore to some of its own member countries and neighbours. Instead, Brussels saves face by targeting smaller, emerging competitors that do not have the resources or the connections to defend themselves. The entire exercise amounts to nothing but theatre for the European taxpayers, at the small countries’ expense in terms of both cost and reputation.

The next scheduled update of the tax blacklist is in October 2022. If the bureaucrats at the Commission are too afraid of going after the actual tax havens, they should just drop their blacklisting act and stop using some of the poorest nations on Earth as scapegoats. Until then, the only evasion taking place will be the Commission avoiding its own accountability.

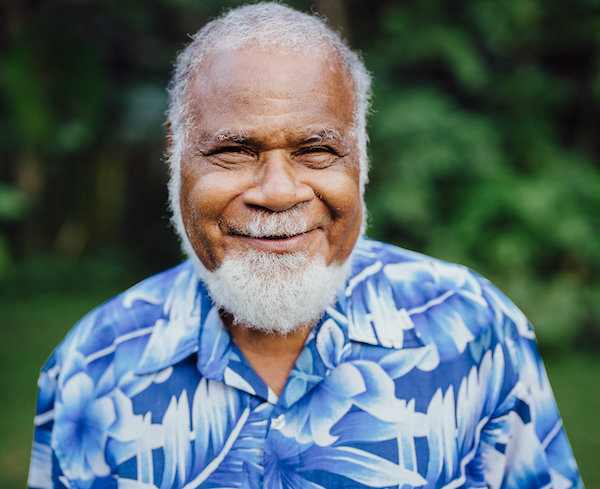

Sela Molisa was first elected as a Member of Parliament in 1983, representing the constituency of Espiritu Santo, his home island. He served in various ministerial portfolios, and has been Governor of the World Bank Group for Vanuatu, and a member of the Bank Group’s Board of Governors.